Hornsey Food Bank in North London supports over 1000 people a week by providing fresh, dried and tined food to those that need it. They operate out of a local church, taking over the main area for service on Thursdays and a small upstairs area for food storage.

After service on a Thursday, the stocktake team would count the leftover inventory, and based on the numbers, would place an order for the following week. Deliveries arrive on Wednesdays where another team of volunteers receives them and sets up the floor for the following days service.

All of this was working well until the discovery of mice in early 2025. The mice were gnawing their way into milk, pasta, biscuits, and almost anything they can get their hands on. Exterminators were called but even so, the team needed a way to protect the food week to week.

The team decided to replace the open plastic crates they were using to store items with sealable clear plastic containers. This did save the food from the mice, but created its own problem.

What’s in a crate?

The team that recorded inventory every week did so by counting crates – e.g. 2.5 crates of pasta, 1 crate of biscuits. They knew roughly how many of each item fit into the standarized crates, so it was trivial to translate crates into individual units. However, with the introduction of containers, counting became exponentially more difficult.

Not only was it hard to work out how many packets of rice were in a clear container, but there were 5 different sizes of clear containers. For several months the team were doing their best to estimate how many of each item was there and as a result stock levels yo-yoed. Some weeks the storage area was bursting with excess inventory and others they were facing stock outs during Thursday service.

This is around the time I started volunteering with the stocktake team and saw the new challenge for myself. I knew in order to fix it, we needed something:

- easy – we couldn’t ask volunteers to count individual bags of rice or pasta every week

- accurate – we needed to know as closely as possible how many items we had on hand

- low-tech – there was no budget for big tools and the volunteers needed something familiar and easy to use

Part 1: A better way to count

The first challenge was how to know how many of each item were in containers. I thought if we could count how many of each item fit in each of the 5 different size containers, we could ask volunteers to log the number of each container rather than the number of crates.

First we labeled each of the different size crates with coloured tape – e.g. a large 35L container has blue tape wrapped around it, the 10L green tape. Then, with the help of a few volunteers, we worked out how many of each item fit into each container – e.g. 38 packets of 1kg rice fit in a blue container.

This system had the benefit of being easy for volunteers doing the tracking, while being accurate enough to allow for better ordering.

Part 2: A better interface

However, the spreadsheet that had been used to track inventory before exploded with complexity with the addition of these new 5 containers. Some items like canned goods were still stored in crates and therefore needed to be counted in crates, some items were stored in sealed containers and some were counted individually. Trying to input that information on a spreadsheet on a phone was too complicated and likely to lead to errors.

I looked into ways to create a better interface for this niche use case, but found either expensive proprietary tools, or things that were too simplistic. The team was well-versed in spreadsheets and didn’t want to jump into cloud databases or bespoke code that would have left them in the lurch if they didn’t have a volunteer with those specific skills.

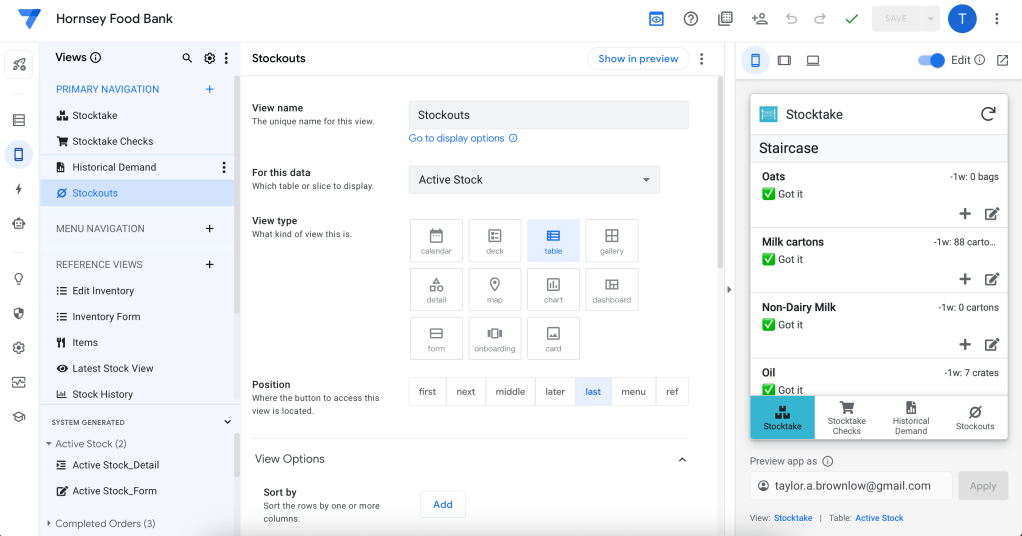

Luckily I happened upon AppSheet – a Google product that creates simple user interfaces that can read, write, and edit Google Sheet Databases.

AppSheet allowed me to customise the inventory input form to ask for the the right units (e.g. crates for canned items, and containers for potential mice fodder).

After a few weeks of testing and improvements with the stocktake team, we finally had a system that could allow us to track accurate inventory week-to-week.

With the help of a short video tutorial and a few in-person live sessions, the app was successfully adopted by the entire 15-person stocktake volunteer team.

Part 3: Storing historical data for better predictions

The last piece of the puzzle was how to capture this data each week so that we can start to see patters and make better ordering decisions. The original spreadsheet that was used to track inventory was reset every week, so there was no historical information stored.

With the AppSheet interface I could easily create new rows of data without the inputter even knowing they were doing it, giving us historical inventory.

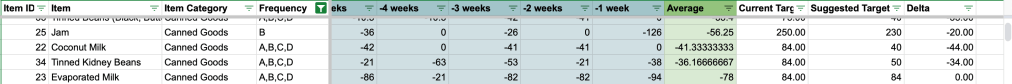

To understand demand, we also needed to get a sense of how much of each item was coming in every week. To do this, I built a sheet specifically to help the person who ordered the food each week. This sheet broke down how much of each item was needed if we were to hit our target inventory levels. Once the orders were placed, and a box ticked, the orders would be saved in another sheet, thus giving us historical orders.

With orders and inventory we were able to estimate demand for each item. With this we could start to make the biggest difference by keeping fewer items on-hand.

Next steps

With a repeatable and accurate process in place, we can continue to take this project even further. For example, with fewer items in storage we will soon be re-arranging the storage area to better accommodate the volunteers who bring items and up and down the stairs before and after service. This will involve thoughtful consideration of where to place the heavier items, consideration of structural concerns, and clear labeling so the new system persists with new volunteers over time.

Additionally, this new system has made the food bank more willing to experiment with new food offerings. Before the fear of stocking out of new items or being stuck with items no one wanted deterred many new offering decisions. However, there are several new items that will be trialed over the coming months.

Lessons Learned

This project was my first with a charity and non-profit, and as such it taught me many lessons I take into all future projects, such as:

- Listen first. At the start the problem was clear – the new plastic containers – but there were many ideas of how to resolve it. It was incredibly helpful for me to talk to almost everyone involved in the problem in order to better understand it and come up with a solution that would work best for all parties.

- Use the tech people know. There are many out of the box solutions to inventory tracking, however they are expensive and would come with their own headaches like extensive training.

- Plan for the future. Charities and non-profits are often run by an ever-changing cadre of volunteers with varying skills. Building any solution means taking that uncertain future skillset into account and building things that will have the highest likelihood of surviving.

Have any questions about this project or how I can help your organisation?

Leave a comment